Introduction

Spring

is defined as an elastic body, whose function is to distort when loaded and to

recover to its original shape when the load is removed.

Objectives of Spring

Following

are the objectives of a spring when used as a machine member:

1. Cushioning,

absorbing, or controlling of energy due to shock and vibration.

Car springs or railway buffers

To control energy, springs-supports and vibration dampers.

2.

Control of motion

Maintaining contact between two elements (cam and its

follower)

In a cam and a follower arrangement,

widely used in numerous applications, a spring maintains contact between the

two elements. It primarily controls the motion.

Creation of the necessary pressure in a friction device (a

brake or a clutch)

A person driving a car uses a brake or

a clutch for controlling the car motion. A spring system keep the brake in

disengaged position until applied to stop the car. The clutch has also got a

spring system (single springs or multiple springs) which engages and disengages

the engine with the transmission system.

Restoration of a machine part to its normal position when

the applied force is withdrawn (a governor or valve)

A typical example is a governor for

turbine speed control. A governor system uses a spring controlled valve to

regulate flow of fluid through the turbine, thereby controlling the turbine

speed.

3.

Measuring forces

Spring balances, gages

4. Storing of energy

In clocks or starters

The clock has spiral type of spring which is wound to coil and then the

stored energy helps gradual recoil of the spring when in operation. Nowadays we

do not find much use of the winding clocks.

Before considering

the design aspects of springs we will have a quick look at the spring materials

and manufacturing methods.

Commonly used spring materials

One of the

important considerations in spring design is the choice of the spring material.

Some of the common spring materials are given below.

·

Hard-drawn wire:

This is cold drawn, cheapest spring steel. Normally used for low stress

and static load. The material is not suitable at subzero temperatures or at

temperatures above 1200C.

·

Oil-tempered wire:

It is a cold drawn, quenched, tempered, and general purpose spring

steel. However, it is not suitable for fatigue or sudden loads, at subzero

temperatures and at temperatures above 1800C.

When we go for highly stressed conditions then alloy steels are useful.

·

Chrome Vanadium:

This alloy spring steel is used for high stress conditions and at high

temperature up to 2200C. It is good for fatigue resistance and long endurance

for shock and impact loads.

·

Chrome Silicon:

This material can be used for highly stressed springs. It offers

excellent service for long life, shock loading and for temperature up to 2500C.

·

Music wire:

This spring material is most widely used for small springs. It is the

toughest and has highest tensile strength and can withstand repeated loading at

high stresses. However, it can not be used at subzero temperatures or at

temperatures above 1200C.

Normally when we talk about springs we will find that the music wire is

a common choice for springs.

·

Stainless steel:

Widely used alloy spring materials.

·

Phosphor Bronze /

Spring Brass:

It has good corrosion resistance and electrical conductivity. That’s the

reason it is commonly used for contacts in electrical switches. Spring brass

can be used at subzero temperatures.

Spring

manufacturing processes

If springs are of

very small diameter and the wire diameter is also small then the springs are

normally manufactured by a cold drawn process through a mangle. However, for

very large springs having also large coil diameter and wire diameter one has to

go for manufacture by hot processes. First one has to heat the wire and then

use a proper mangle to wind the coils.

Helical spring

The figures below show the schematic representation

of a helical spring acted upon by a tensile load F (Fig.7.1.1) and compressive

load F (Fig.7.1.2). The circles denote the cross section of the spring wire.

The cut section, i.e. from the entire coil somewhere we make a cut, is

indicated as a circle with shade.

If we

look at the free body diagram of the shaded region only (the cut section) then

we shall see that at the cut section, vertical equilibrium of forces will give

us force, F as indicated in the figure. This F is the shear force. The torque

T, at the cut section and it’s direction is also marked in the figure. There is

no horizontal force coming into the picture because externally there is no

horizontal force present. So from the fundamental understanding of the free

body diagram one can see that any section of the spring is experiencing a

torque and a force. Shear force will always be associated with a bending

moment.

However, in an ideal situation, when force is acting at the

centre of the circular spring and the coils of spring are almost parallel to each

other, no bending moment would result at any

section of the spring ( no moment arm), except torsion and

shear force. The Fig.7.1.3 will explain the fact stated above.

Stresses

in the helical spring wire:

From the free body diagram, we have found out the direction

of the internal torsion T and internal shear force F at the section due to the

external load F acting at the centre of the coil.

The cut sections of the spring, subjected to tensile and

compressive loads respectively, are shown separately in the Fig.7.1.4 and

7.1.5. The broken arrows show the shear stresses ( τT )

arising due to the torsion T and solid arrows show the shear stresses ( τF ) due

to the force F. It is observed that for both tensile load as well as

compressive load on the spring, maximum shear stress (τT + τF)

always occurs at the inner side of the spring. Hence, failure of the spring, in

the form of crake, is always initiated from the inner radius of the spring.

The radius

of the spring is given by D/2. Note that D is the mean diameter of the spring.

The torque T acting on the spring is

(7.1.1)

If d is the diameter of the coil wire

and polar moment of inertia the shear stress in the spring wire due to torsion

is

Average

shear stress in the spring wire due to force F is

Therefore, maximum shear stress the

spring wire is

The above equation gives maximum shear

stress occurring in a spring. Ks is the shear stress correction

factor.

Stresses in

helical spring with curvature effect:

What is curvature effect? Let us look at a small section of a

circular spring, as shown in the Fig.7.1.6. Suppose we hold the section b-c

fixed and give a rotation to the section a-d in the anti clockwise direction as

indicated in the figure, then it is observed that line a-d rotates and it takes

up another position, say a'-d'. The inner length a-b being smaller compared to

the outer length c-d, the shear strain γi at the inside of the spring

will be more than the shear strain γo at the outside of the spring.

Hence, for a given wire diameter, a spring with smaller diameter will

experience more difference of shear strain between outside surface and inside

surface compared to its larger counter part. The above phenomenon is termed as

curvature effect. So more is the spring index (C=D/d) the lesser will be the

curvature effect. For example, the suspensions in the railway carriages use

helical springs. These springs have large wire diameter compared to the

diameter of the spring itself. In this case curvature effect will be

predominantly high.

To take care of the curvature effect, the earlier equation

for maximum shear stress in the spring wire is modified as,

Where,

KW is

Wahl correction factor, which takes care of both curvature effect and shear

stress correction factor and is expressed as,

Deflection

of helical spring:

Consider

a small segment of spring of length ds, subtending an angle of dβ at the center

of the spring coil as shown in Fig.7.1.7(b). Let this small spring segment be

considered to be an active portion and remaining portion is rigid. Hence, we

consider only the deflection of spring arising due to application of force F.

The rotation, dφ, of the section a-d with respect to b-c is given as,

The

rotation, dφ will cause the end of the spring O to rotate to O', shown in Fig. 7.1.7(a).

From geometry, O-O' is given as,

However,

the vertical component of O-O' only will contributes towards spring deflection.

Due to symmetric condition, there is no lateral deflection of spring, ie, the

horizontal component of O-O' gets cancelled.

The vertical component of O-O', dδ, is

given as,

Total

deflection of spring, δ, can be obtained by integrating the above

expression for entire length of the spring wire.

Simplifying

the above expression we get,

Where,

N is the number of active turns and G is the shear modulus of

elasticity. Now what is an active coil? The force F cannot just hang in space,

it has to have some material contact with the spring. Normally the same spring

wire e will be given a shape of a hook to support the force F. The hook etc.,

although is a part of the spring, they do not contribute to the deflection of

the spring. Apart from these coils, other coils which take part in imparting

deflection to the spring are known as active coils.

The

above equation is used to compute the deflection of a helical spring. Another

important design parameter often used is the spring rate. It is defined as,

Here

we conclude on the discussion for important design features, namely, stress,

deflection and spring rate of a helical spring.

Design

of helical spring for variable load

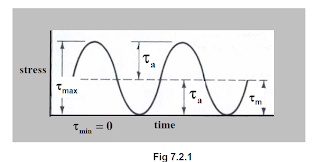

In

the case of a spring, whether it is a compression spring or an extension

spring, reverse loading is not possible. For example, let us consider a

compression spring placed between two plates. The spring under varying load can

be compressed to some maximum value and at the most can return to zero

compression state (in practice, some amount of initial compression is always

present), otherwise, spring will loose contact with the plates and will get

displace from its seat. Similar reason holds good for an extension spring, it

will experience certain amount of extension and again return to at the most to

zero extension state, but it will never go to compression zone. Due to varying

load, the stress pattern which occurs in a spring with respect to time is shown

in Fig.7.2.1. The load which causes such stress pattern is called repeated

load. The spring materials, instead of testing under reversed bending, are

tested under repeated torsion.

From

Fig.7.2.1 we see that,

Where,

τa is

known as the stress amplitude and τm is known as the mean stress

or the average stress. We know that for varying stress, the material can

withstand stress not exceeding endurance limit value. Hence, for repeated

torsion experiment, the mean stress and the stress amplitude become,

(7.2.2)

Soderberg

failure criterion :

The modified Soderberg diagram for repeated stress is shown

in the Fig 7.2.2.

The stress

being repeated in nature, the co-ordinate of the point a is ( τe/2, τe/2). For safe

design, the design data for the mean and average stresses, τa and τm respectively, should

be below the line a-b. If we choose a value of factor of safety (FS), the line

a-b shifts to a newer position as shown in the figure. This line e-f in the

figure is called a safe stress line and the point A (τm,τa) is a typical safe design point.

Considering

two similar triangles, abc and Aed respectively, a relationship

between the stresses may be developed and is given as,

where

τY is

the shear yield point of the spring material.

In simplified form, the equation for

Soderberg failure criterion for springs is

The

above equation is further modified by considering the shear correction factor,

Ks and

Wahl correction factor, Kw. It is a normal practice to multiply τm by Ks and to

multiply τa

by Kw.

The above equation for Soderberg

failure criterion for will be utilized for the designing of springs subjected

to variable load.

Estimation

of material strength

It is

a very important aspect in any design to obtain correct material property. The

best way is to perform an experiment with the specimen of desired material.

Tensile test experiments as we know is relatively simple and less time

consuming. This experiment is used to obtain yield strength and ultimate

strength of any given material. However, tests to determine endurance limit is

extremely time consuming. Hence, the ways to obtain material properties is to

consult design data book or to use available relationships, developed through

experiments, between various material properties. For the design of springs, we

will discuss briefly, the steps normally used to obtain the material

properties.

One of the relationships to find out

ultimate strength of a spring wire of diameter d is,

For some selected materials,

which are commonly used in spring design, the values of As and ms are

given in the table below.

The

above formula gives the value of ultimate stress in MPa for wire diameter in

mm. Once the value of ultimate strength is estimated, the shear yield strength

and shear endurance limit can be obtained from the following table developed

through experiments for repeated load.

Hence,

as a rough guideline and on a conservative side, values for shear yield point

and shear endurance limit for major types of spring wires can be obtained from

ultimate strength as,

With

the knowledge of material properties and load requirements, one can easily

utilize Soderberg equation to obtain spring design parameters.

Types

of springs

There are mainly two types of helical springs, compression

springs and extension springs. Here we will have a brief look at the types of

springs and their nomenclature.

1. Compression springs

Following are the types of compression

springs used in the design.

In the

above nomenclature for the spring, N is the number of active coils,

i.e., only these coils take part in the spring action. However, few other coils

may be present due to manufacturing consideration, thus total number of coils, NT may

vary from total number of active coils.

Solid

length, LS

is that length of the spring, when pressed, all the spring

coils will clash with each other and will appear as a solid cylindrical body.

The

spring length under no load condition is the free length of a spring.

Naturally, the length that we visualise in the above diagram is the free length.

Maximum amount of compression the

spring can have is denoted as δmax, which is calculated from the design

requirement. The addition of solid length and the δmax should be sufficient

to get the free length of a spring. However, designers consider an additional

length given as δ allowance. This allowance is provided to avoid clash

between to consecutive spring coils. As a guideline, the value of δ allowance is

generally 15% of δmax.

The

concept of pitch in a spring is the same as that in a screw.

The top and

bottom of the spring is grounded as seen in the figure. Here, due to grounding,

one total coil is inactive.

In

the Fig 7.2.5 it is observed that both the top as well as the bottom spring is

being pressed to make it parallel to the ground instead of having a helix

angle. Here, it is seen that two full coils are inactive.

It

is observed that both the top as well as the bottom spring, as earlier one, is

being pressed to make it parallel to the ground, further the faces are grounded

to allow for proper seat. Here also two full coils are inactive.

2. Extension

springs

Part

of an extension spring with a hook is shown in Fig.7.2.7. The nomenclature for

the

extension spring is given below.

Body length, LB: d

(N + 1)

Free length, L : LB +

2 hook diameter.

here, N stands for the number of active

coils. By putting the hook certain amount of stress concentration comes in the

bent zone of the hook and these are substantially weaker zones than the other

part of the spring. One should take up steps so that stress concentration in

this region is reduced. For the reduction of stress concentration at the hook

some of the modifications of spring are shown in Fig 7.2.8.

Buckling

of compression spring

Buckling is an instability that is normally shown up when a

long bar or a column is applied with compressive type of load. Similar

situation arise if a spring is too slender and long then it sways sideways and

the failure is known as buckling failure. Buckling takes place for a

compressive type of springs. Hence, the steps to be followed in design to avoid

buckling is given below.

Free length (L) should be less than 4 times the coil

diameter (D) to avoid buckling for most situations. For slender springs central

guide rod is necessary.

A guideline

for free length (L) of a spring to avoid buckling is as follows,

For steel,

Where, Ce is

the end condition and its values are given below

Ce End condition

2.0 fixed and free

end

1.0 hinged at both

ends

0.707 hinged and fixed end

0.5 fixed at both ends

If

the spring is placed between two rigid plates, then end condition may be taken

as 0.5. If after calculation it is found that the spring is likely to

buckle then one has to use a guide rod passing through the center of the spring

axis along which the compression action of the spring takes place.

Spring surge (critical frequency)

If a

load F act on a spring there is a downward movement of the spring and due to

this movement a wave travels along the spring in downward direction and a to

and fro motion continues. This phenomenon can also be observed in closed water

body where a disturbance moves toward the wall and then again returns back to

the starting of the disturbance. This particular situation is called surge of

spring. If the frequency of surging becomes equal to the natural frequency of

the spring the resonant frequency will occur which may cause failure of the

spring. Hence, one has to calculate natural frequency, known as the fundamental

frequency of the spring and use a judgment to specify the operational frequency

of the spring.

The fundamental frequency can be

obtained from the relationship given below.

Fundamental

frequency :

Both ends within

flat plates

One

end free and other end on flat plate.

Both ends within

flat plates

One

end free and other end on flat plate.

Where,

K: Spring rate

WS :

Spring weight =

WS :

Spring weight =

and d is

the wire diameter, D is the coil diameter, N is the number of

active coils and γ is the specific weight of spring material.

The

operational frequency of the spring should be at least 15-20 times less than

its fundamental frequency. This will ensure that the spring surge will not

occur and even other higher modes of frequency can also be taken care of.

Spring Manufacturing Process